David Heim is a veteran book and magazine editor specializing in woodworking. After a 28-year career at Consumer Reports, he moved to Fine Woodworking magazine. David has been writing about and teaching SketchUp for over four years, and says he never begins any project until he has previewed it in SketchUp first. This is one of several upcoming SketchUpdate guest posts from David on modeling principles for woodworkers.

I first heard the phrase clean modeling from Dave Richards at 3D Basecamp 2014. As Dave explained it to me later, clean modeling is a simple concept that basically means, “learn to sweat the small stuff.” If the model isn’t “clean,” small flaws could interfere with the changes you or someone else may want to make in the future. Let’s take a closer look at clean modeling principles via a Shaker trestle table I did a few years back. It looks pretty good, right? Actually, it’s a good example of why clean modeling is important.

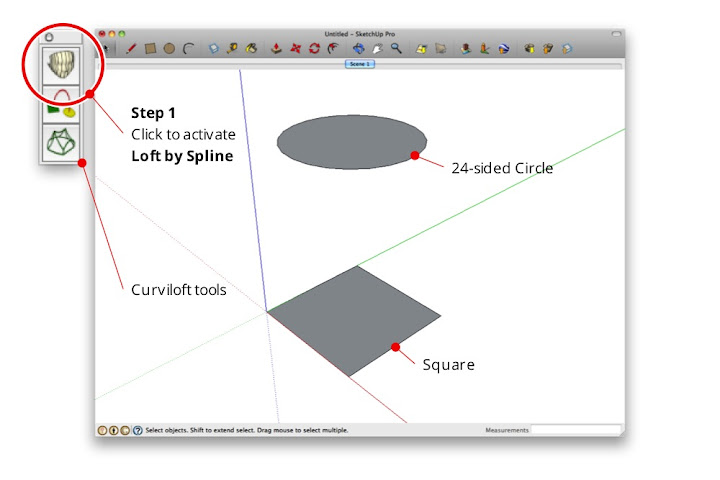

|

| Although this model of a Shaker table looks pretty good, it actually contains a number of flaws; finding and fixing them is what clean modeling is all about. |

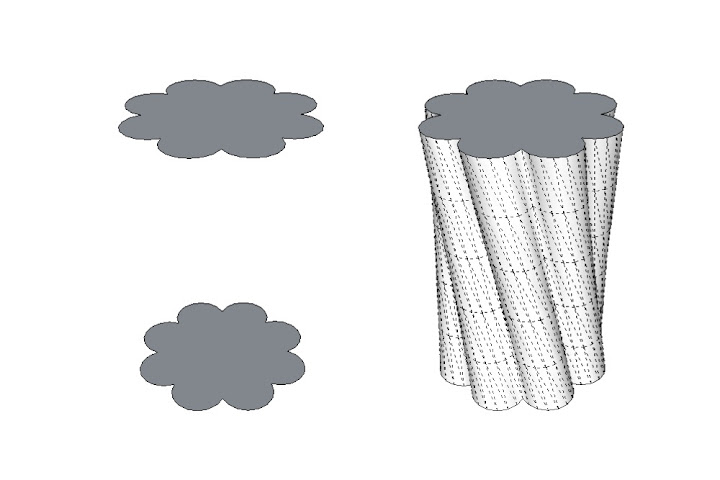

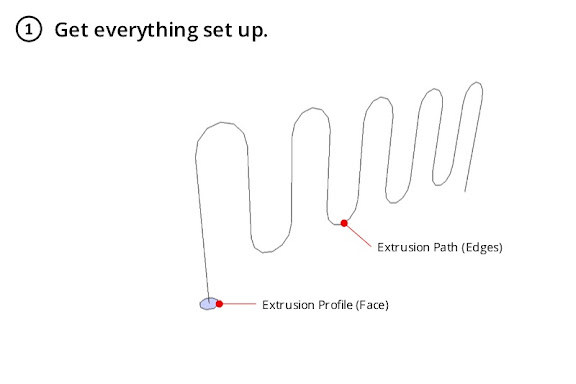

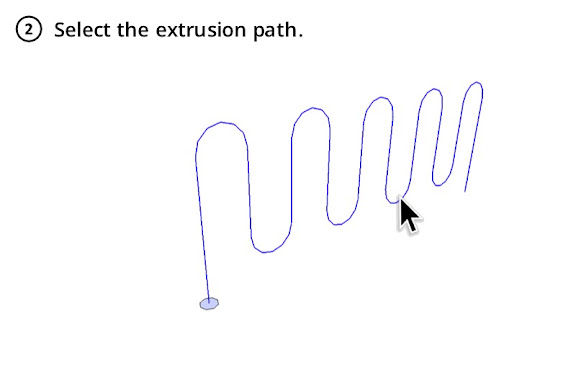

Missing Faces. I thought enough of the trestle table model to share it on the SketchUcation woodworking forum. Someone quickly cut me down to size, pointing out that my turned legs were missing faces. It’s a good thing no one looked closer. In fact, there were several problems with the model. Let’s begin with the missing faces. It happened because I was working with small geometry at a 1:1 scale. I could have saved face, so to speak, if I had scaled up the leg profile before extruding it.

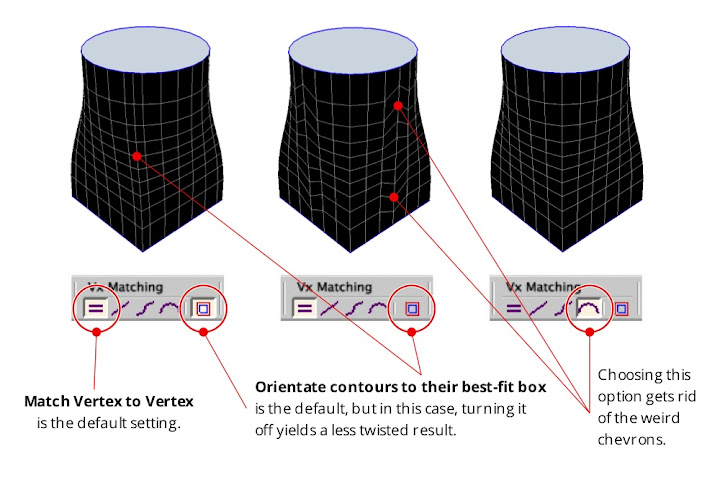

|

| The blue areas (left side) show where faces were not created properly. The right side shows the successful result of the scaled up Follow Me technique. |

You can heal these faces by tracing over some of the edges with the Line tool, but it’s better to scale up certain components before using Follow Me or running Intersect Faces. Dave Richards typically copies a component to be extruded or intersected, scales it up 100x or even 1000x, and then edits the copy. After that, he deletes the copy; the original will show the edits properly. Generally, I’ve found this scaling method ensures a model won’t wind up with small missing faces.

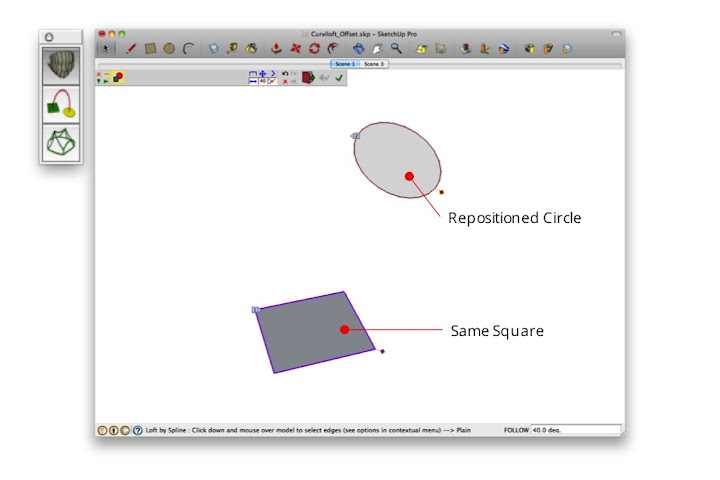

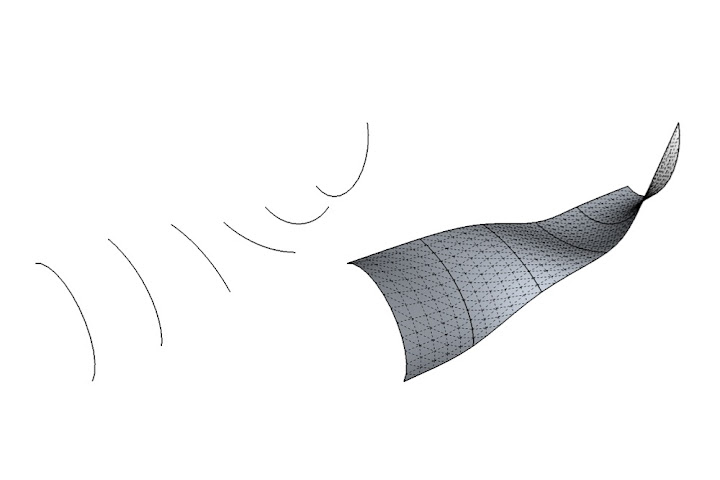

A closer look. Inspecting the bottom of the arched feet reveals more small problems. If I run ThomThom’s Solid Inspector extension, it shows me a stray line at one corner. It’s only about 1/64” long, but it shouldn’t be there. The same goes for a sliver of a stray face on the opposite corner. Extraneous lines and faces like these can pop up sometimes when performing certain tasks — like Intersect Faces mentioned above. These little lines are hard to see, of course. I could say, “So what? No one will ever see them.” Maybe, but I need to get rid of them if I want a clean model.

Ed. Note: ThomThom recently released Solid Inspector². Also, try “StrayLines.rb” from www.smustard.com.

|

| The Solid Inspector extension reveals a minuscule stray line at the base of the foot. This extension is a useful tool for identifying extraneous geometry that could be erased. |

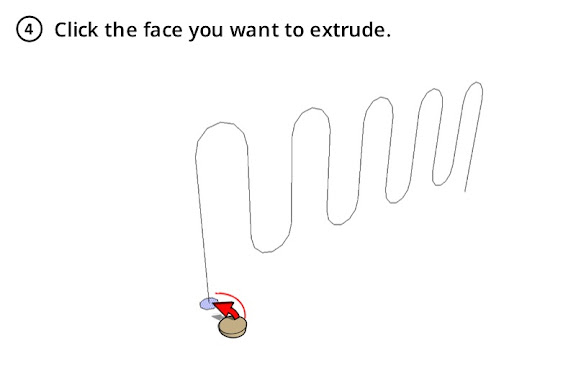

Orient faces. Obviously, visible faces must be oriented properly. But the same goes for faces that aren’t meant to be seen: the sides of holes, recesses, mortises, and the like. As you create those elements, take the time to be sure the correct face is showing. If a surface is facing the wrong way, you can right-click on it and choose Reverse Faces.

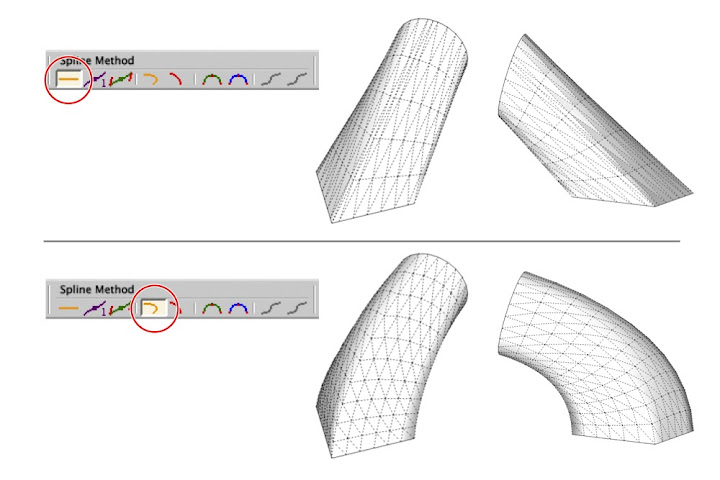

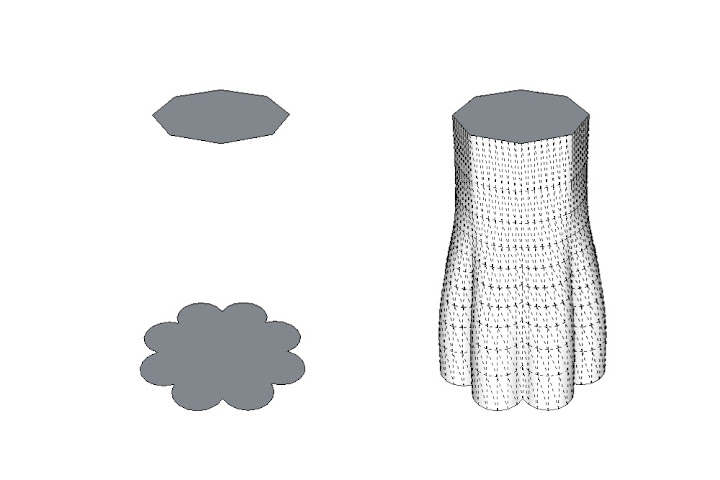

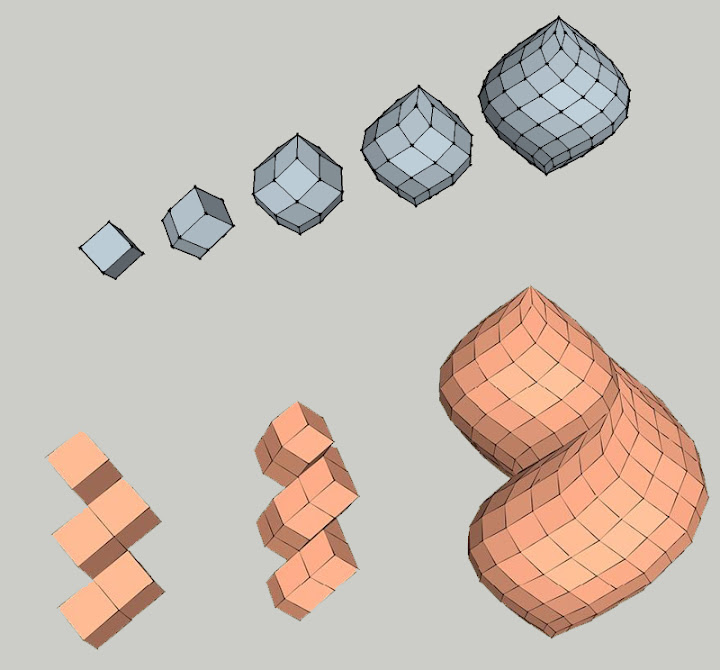

Soften/Smooth curved faces. Often, when you Push/Pull a shape that results in a curved face, you’ll also create edges separating the facets of the curve. You can hide those edges, but the face will still look faceted. It’s better to eliminate the edges with the Soften/Smooth Edges technique.

|

| Hiding the edges on a curved face leaves the surface looking faceted (middle object). For a truly smooth face, use Soften/Smooth Edges. |

Set component axes. If a component doesn’t perfectly align to the axes, be sure to set the axes when you create the component. This is especially important if you’re planning to use the CutList extension. It relies on the size of the bounding box to reckon the size of the component. An oversized bounding box will lead to inaccuracies in the cutlist.

Clean-up. Finally, reduce the file size: purge unused components, use multiple copies of components instead of numerous groups, and compress textures. ThomThom’s CleanUp³ extension helps expedite this process. If my advice strikes you as too obvious, that probably means your models are pretty clean already.

Guest authored by David Heim